“They don’t intend to enter Ukrainian higher educational institutions. Neither boys nor girls. There are about 90% of such children in some classes. Theoretically speaking, 27 out of 30 will leave. Most likely, forever”. This is a quote from the post by the founder of a private distance learning school, which went viral last year. This post was related to a specific, rather unique school, but it raised a relevant discussion for the umpteenth time: where do we stand in terms of demographic issues? What is in store for the country, whose young people are leaving? And what is the real scope of the definitely urgent problem?

This investigation has become possible thanks to the participants of the NGL.media community, who have access to special content and possibilities.

16-year-old Mykyta Zhuravliov, his 17-year-old sister Polina and their mother have been living in the town of Sanitz in northern Germany. Teenagers study at a typical local school – in the morning, they come to their classes, which end in the afternoon. At the same time, Mykyta and Polina study the Ukrainian school curriculum via homeschooling. It means that they are exempt from attending lessons, but twice a year, they must undergo online testing at their Kyiv school to confirm the level of their knowledge.

“Two weeks after our coming to Germany, our neighbour, a German man, took the kids and arranged their study at the school his daughter was attending. At first, everything was very interesting and unusual. Surprisingly, kids went to school with pleasure,” Oksana Zhuravliova, the mother of two teenagers, told NGL.media. “It was difficult to combine the study in two countries, but we decided not to stop at one variant, because life is very changeable, as it has turned out.”

Homeschooling, used by Oksana Zhuravliova’s children to study, is one of three available study forms Individual form of study in the Ukrainian school education system envisages three forms: externship, homeschooling, and pedagogical patronage for pupils who can attend lessons in Ukraine neither offline nor online. It is convenient because this format allows them to study in the country of their residence and still receive a secondary school diploma in a Ukrainian school.

“Just in case [children study in a Ukrainian school] because we don’t know how long we will still have temporary protection here, and how it will all end,” Anna Shpak explains to NGL.media, she lives near Wexford in Ireland with her three children (aged 14, 15, and 16). She says that many children from her Ukrainian community there have already entered local universities, but she is not sure yet which choice her children will make. Due to this doubtfulness, teenagers still combine studies in two schools to have a chance for higher education anyway.

The experience of these two families is not unique. Most countries, accepting Ukrainians, make them give their kids to local schools. But not everybody intends to stay there forever, so they often continue their study at a Ukrainian school. According to the information of the Ministry of Education, at present, 9.3% Ukrainian pupils study abroad As per the data of the State Statistics Service, at the beginning of the study year 2024-2025, Ukrainian secondary education institutions had a total of 3,743,887 pupils – these are about 345 thousand children.

It is important to understand that the Ministry of Education considers only the pupils who still remain in the Ukrainian system of education. In other words, these 345 thousand pupils are the minimal estimate, because after leaving abroad, many children terminate their studies at a Ukrainian school altogether.

“Kids have adjusted to the local school fast, and their study has been going well. But due to a great load, they had to leave the Ukrainian school. The choice in favour of a Polish school was obvious, because I decided that we will not come back until the war is over. I don’t want to risk the lives of my children. And despite their missing Ukraine, they are afraid to come back too because they remember the explosions,” Inna V. told NGL.media, last year she took her three kids to Poland from the Khmelnytskyi region. Now her two older kids study at a Polish school, and the youngest one goes to the local kindergarten.

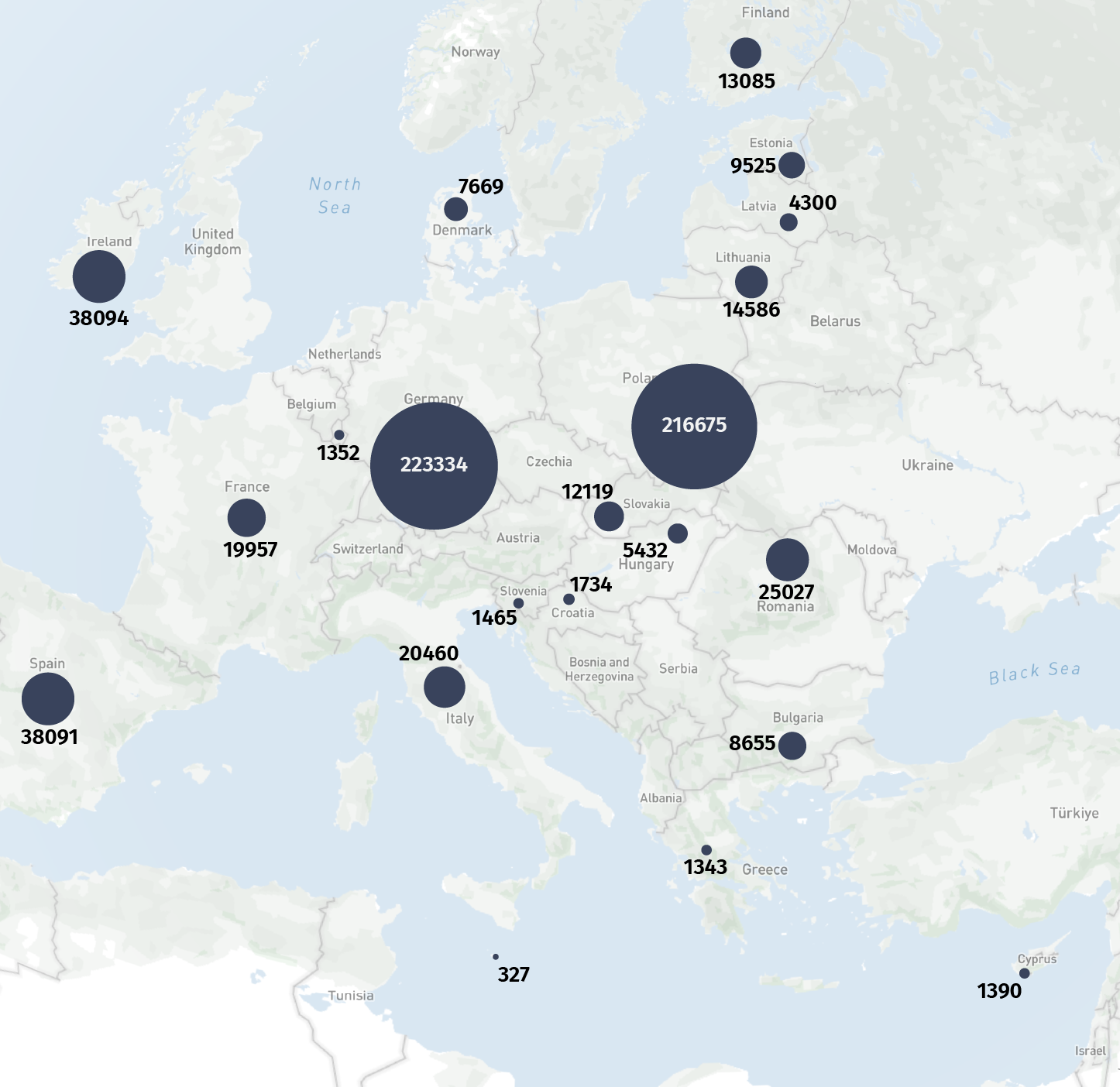

The investigation by UNESCO demonstrates that as of 2024, about 665 thousand Ukrainian pupils studied abroad, and this figure is not comprehensive either, because it considers only the EU member states, and not even all the countries Ukrainians have migrated to. Only 29% of these pupils combine their studies in both countries, and 16% rely only on Ukrainian online education. If this tendency is extrapolated to the countries, not considered by UNESCO, it is possible to assume that a total of about 720 thousand Ukrainian pupils are abroad.

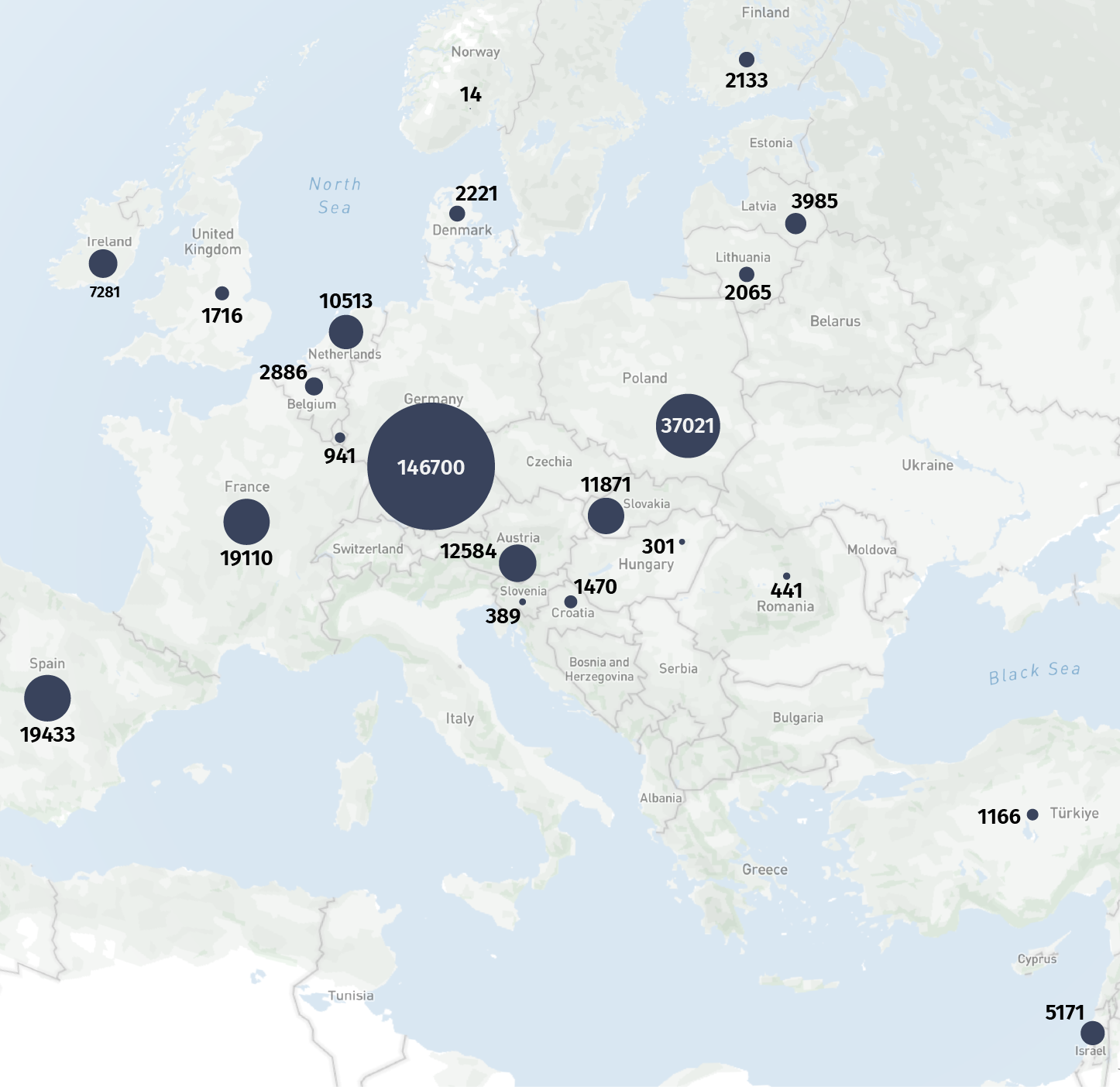

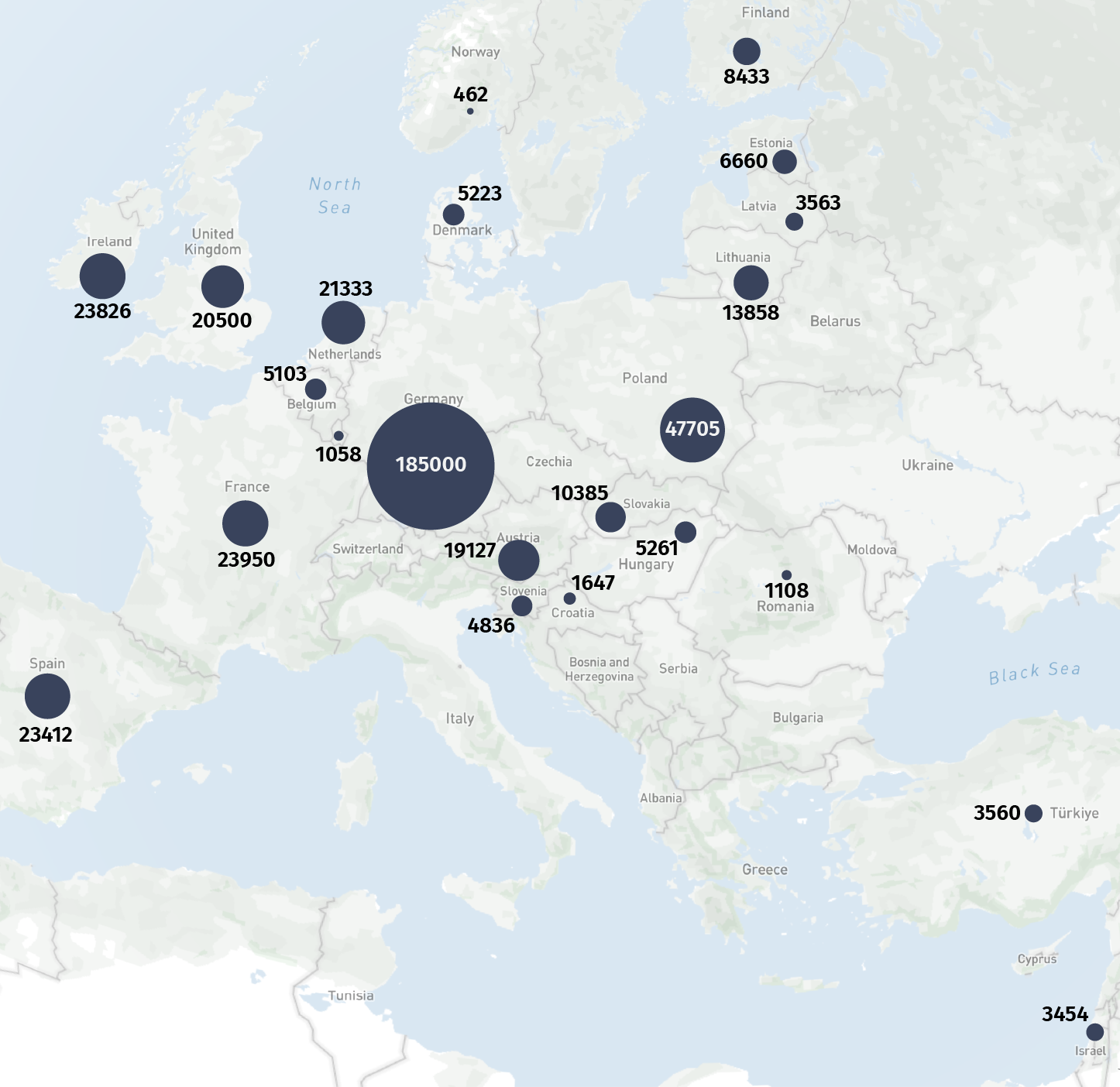

As per the data of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, about 1.4 million displaced Ukrainians in the world are children aged 3-17. These statistical data cover both the children of Inna V., who abandoned their Ukrainian school, and the kids of Oksana Zhuravliova and Anna Shpak, who study at two schools at the same time. Now, most pupils and preschoolers from Ukraine live in Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Great Britain.

Number of Ukrainian students officially studying in European schools

Number of Ukrainian students officially studying in European schools

Number of Ukrainian students officially studying in European schools

Not only 17-year-old boys are leaving, but girls are too

The participants of the investigation programme RAI for Ukraine The programme is conducted by the Centre for Responsible AI at the New York University in cooperation with the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv analysed the difference between the place of registration for NMT participants the National Multi-Subject Test, required to enter higher educational institutions in Ukraine and the place where they actually were taking this test the corresponding datasets are open and available on the website of the Ukrainian Centre for Educational Quality Assessment. By doing so, they learned that in 2022, 23.5 thousand school graduates (10% of the total) took this test abroad. And 32% of graduates didn’t even register for the NMT, which is required to enter Ukrainian universities.

“We do understand that the graduates, staying abroad, might take this exam just in case. It does not mean that all of them think about entering a Ukrainian university. So those 32%, who haven’t taken the NMT at all, can be added to some of those who have passed it but haven’t entered any institution in Ukraine,” explains Tetiana Zakharchenko from the Ukrainian Catholic University, one of the investigation authors, in a conversation with NGL.media. “So, in reality, the losses are higher; we just operate with incomplete data. So yes, rather a large percentage of graduates actually don’t consider entering Ukrainian universities either from the standpoint of safety or closed borders.”

Last October, in his speech in the Parliament, Oksen Lisovyi, the Minister of Education, said that many pupils of the 10th-11th grades, especially boys, were leaving Ukraine. Now, the Minister states that though this tendency remains, it doesn’t pose a threat.

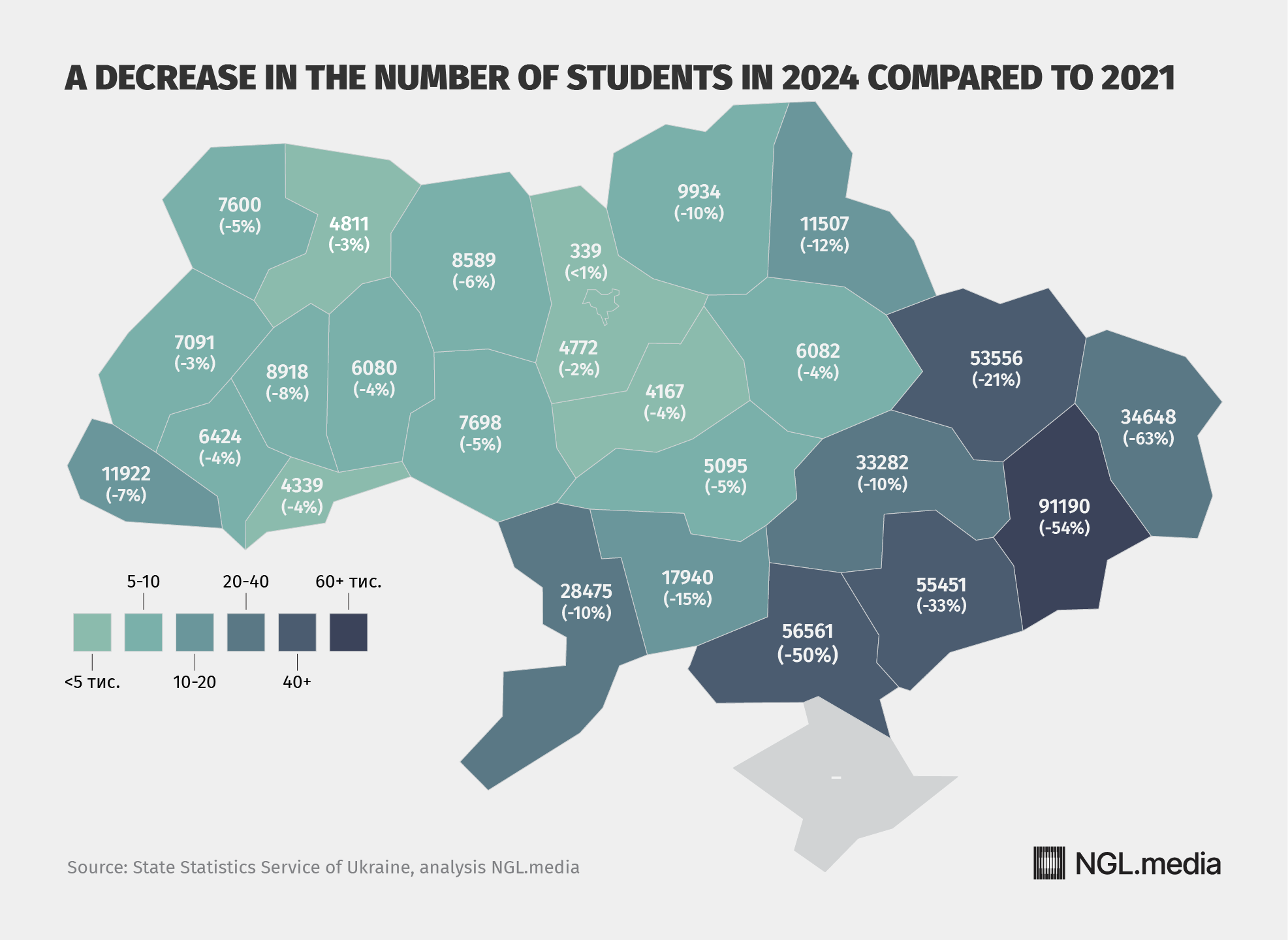

The Ministry of Education gave NGL.media the data about the number of pupils in grades 8-12 in 2021-2025. We compared in what way the number of pupils in classes changes from one year to another, i.e. how many eighth-graders went to the 9th grade, to the 10th grade and so on. There is also an actual tendency for several per cent of the pupils (2-4%) not to progress to the next class year, resulting in them leaving school. It doesn’t necessarily mean that all these children have left Ukraine, but a considerable part of them might have.

When we are discussing who these school graduates are, willing to leave Ukraine, the first thought to come to mind is that these are 17-year-old boys who want to take advantage of the chance to cross the border till reaching 18, the age after which it is prohibited to leave Ukraine in times of the martial law. After all, the hypothesis about the massive departure of 17-year-old boys from the country was a starting point for this investigation.

However, it looks like it is not only boys who leave Ukraine; girls do too. According to the data of the Ministry of Education, in general, the number of girls in high school is increasing each year, but now the difference in genders is rather insignificant (1-2%). Among school graduates, this difference may reach 10% the data of 2022, the investigation of RAI for Ukraine.

“Teenagers are socially dependent, they look at their peers, and if their friends go somewhere, it may trigger a chain reaction. So, it is not strange that girls leave along with the boys,” Tetiana Zakharchenko from the UCU explains.

The main reason for high school pupils to leave abroad is still an issue of safety – it covers both the worry of parents about a possible decrease of the drafting age down to 18 and the general concern about the life of children in a country at war.

“It is also an issue of no socialisation which is a key problem today and one of the arguments why both boys and girls go abroad – because abroad, children study offline, and it is a different approach,” Tetiana Kovryha, the Director of GoGlobal Educational Foundation, explains in the conversation with NGL.media. “And here in Ukraine, we can’t have 100% offline. We obviously lack proper shelters to protect a sufficient number of children.”

Similar thinking makes many graduates of Ukrainian schools choose higher educational institutions in Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic and other countries even after passing the NMT.

“Moreover, ten years ago, people viewed European education as a chance to find their place under the sun: to find a cool job, to go [to work] for a nice company, etc., and they chose only good universities. Now, they go even to some little town in the Czech Republic or Poland, and it is a bad tendency because a provincial institution in Europe is definitely not better than a good Ukrainian university,” Volodymyr Strashko, the founder of Unicorn School for distance learning, believes.

In 2024, 197 thousand students entered the higher educational institutions of Ukraine, which is the lowest index in the last nine years. Reacting to this tendency, some universities are trying to stimulate the return of applicants from abroad. For instance, the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) offers the applicants, willing to come back to Ukraine, full tuition coverage and partial compensation for campus accommodation.

As per Andrii Sidliarenko, the Rector’s Advisor on Student Development and Alumni Relations of the Kyiv School of Economics, the applicants, willing to return to Ukraine to study, are offered full tuition coverage and partial compensation for living on the campus.

“A total of 423 students are enrolled in our grant programmes. This number includes the ones who have received a grant by the Come Back Home programme,” Andrii Sidliarenko, the Rector’s Advisor on Student Development and Alumni Relations of the Kyiv School of Economics, explained to NGL.media. “There is some gender imbalance among these students. Now, about 58% of students in all the grant programmes are girls, and 42% – boys.”

Deficit in the labour market

According to the data of the State Statistics Service, at the beginning of 2024-2025 study year, the education system of Ukraine enrolled a total of 3.74 million pupils in all the forms of studies. This is the lowest number in the last 30 years. This tendency towards a decrease in the number of children and young people in Ukraine will only increase which, among other things, is proved by sociological surveys.

At the end of 2024, the Centre for Economic Strategy conducted an investigation, the results of which demonstrated that as of now, less than half of Ukrainians abroad intend to come back to Ukraine. The main factors, keeping them from returning, are not only the war but also economic factors: uncertainty, destroyed housing, low standard of living, and difficulties in finding a job.

Also, as sad as it is, there is a common opinion in society, which is sometimes well-grounded, that European education is better and of higher quality, while Ukrainian universities are too corrupted.

“At present, I see a successful future for my daughter in Poland. Because of the war and because there are more chances for her to enter a university. With nice grades, the doors are open everywhere. In Ukraine, you have to pay for everything,” Natalia Horbashchenko, a mother of a 17-year-old pupil from the Sumy region who left for Poland at the beginning of the invasion in 2022, says in a conversation with NGL.media. “My older daughter was applying to the Kharkiv Aviation Institute, but good grades didn’t help her get into the programme for free, because the country allocates too few budget-paid places. Perhaps something will change in the future, but now she doesn’t intend to return to Ukraine even after the war ends. Many of her acquaintances don’t plan to return either.”

If the number of students in Ukraine tends to decrease further on, it will create new challenges not only for the higher education system but for the labour market as well. The deficit of qualified personnel, especially those in technical professions, was already felt even prior to the full-scale war, and now, with the outflow of both students and teachers abroad, it may increase considerably.

The state must undertake systemic efforts to encourage school graduates to enrol in Ukrainian universities. The families, coming back to Ukraine, have to see the perspectives of receiving quality education for their children. And although the Ministry of Education simplifies school education for those who live abroad For instance, since 2024, the Ministry of Education and Science launched a possibility of distance learning for pupils abroad using a shortened educational programme, which, among other things, envisages re-crediting of grades for the subjects the children studied abroad, but it doesn’t help much yet.

“Talking about pupils, it is really important to try to have as many of them as possible study the subjects, not taught in the recipient countries, online. To study the subjects not taught there additionally: the Ukrainian Language, Literature, the History of Ukraine – this is really necessary. Some measures could be taken to encourage participation, including even offering prizes for the best pupils. So, it is important to maintain relations with parents, children, to demonstrate that the country needs these people,” says Oleksii Pozniak, a sociologist from the Institute for Demography and Social Studies of the NAS of Ukraine in a conversation with NGL.media.

He believes that after the war ends, Ukraine has to draw on the experience of other countries to bring at least some people home.

“The most useful experience for Ukraine is that of the Balkan countries, which are similar to us in their mentality and [relatively] recently lived through war conflicts. Different methods [for bringing people back] were used there, including the organisation of temporary trips for people to see, where they can go to live, which accommodation they can receive, and where they can find a job. And it stimulated people to make a more substantiated decision about returning or continuing to live abroad,” Oleksii Pozniak believes.

The author Kateryna Rodak, editor Oleh Onysko, infographics Nazarіі Tuziak, translation Nelya Plakhota, illustration Marta Kharkovets